Tara Stevens, CI and CT, NAD III & Amy Schilling, CI and CT

Whether working as mentors, colleagues, interpreters, or as interpreter-educators, we believe in and have seen the benefits of service; we not only encourage this but strive to model community involvement for our students.

Situational or authentic learning is a way for students to gain real world experiences through messy learning opportunities. Messy learning mimics experiences likely to be encountered in the

workplace and marked with more gray areas than clearly defined boundaries. Opportunities for messy learning can happen in the classroom, providing a foundation when students go out for real world experiences. Students need experience with contextualizing information according to situational cues in addition to discourse strategies. Offering practice in classroom situations can help provide a framework for these foundational skills (Kiraly, 2000). Field experience is an important part of the learning process for interpreting students as a way to build on these foundational skills learned in the classroom. Furthermore, engagement in community service is an authentic type of field experience that fosters intrinsic learning.

There are many forms of service that engender community involvement and our focus is mainly on service learning. This pedagogical approach offers a way to instill the value of service in a structured way while immersing students in the Deaf community. Service learning can be an excellent way for interpreting students to gain experience related to ethical decision making as active participants in service learning activities.

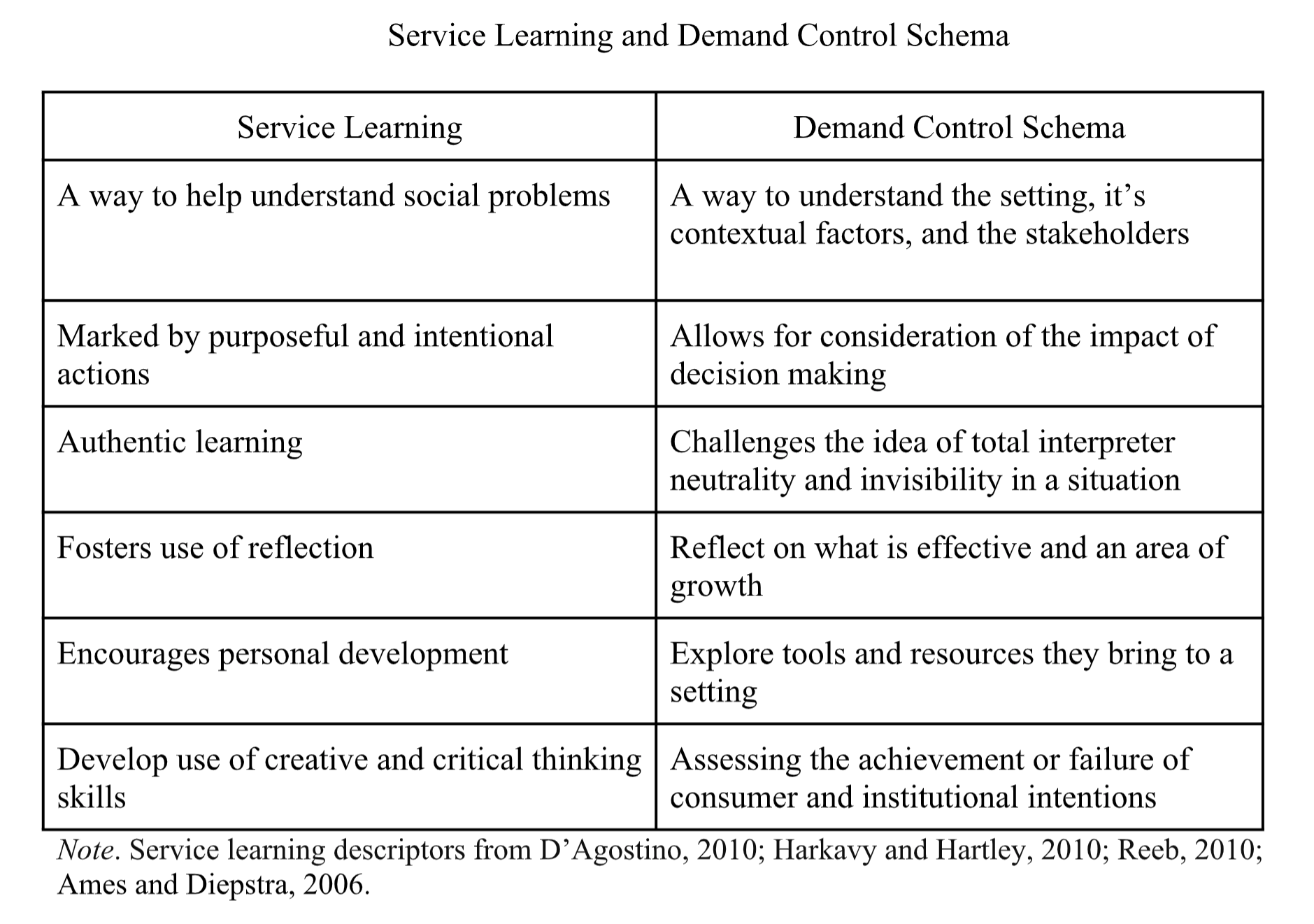

Service Learning and the Demand Control Schema

Service learning when combined with the Demand Control Schema, a framework encapsulating the overall interpreting process, provides additional tools for understanding the work of interpreters. Whether involved in service learning or interpreting, effective decision making is a critical part of either endeavour. Collaborative learning environments may consist of students, practitioners, teachers, mentors, or community partners where participants can benefit from feedback intended to be “useful and empowering” regarding decision making (Witter-Merithew, 2001, p. 2). Frequently, working interpreters are faced with the “it depends” response to decision making and this holds true for interpreting students engaging in service learning opportunities. Demand Control Schema (DC-S) provides a way to address the common “it depends” or a way to fill-in-the-blanks of the unfolding interaction while addressing critical contextual, cultural, and linguistic factors (Dean and Pollard, 2011). The opportunity to practice ethical decision making while engaged in service learning provides students and beginning interpreters with meaningful and authentic experiences that lay the foundation for future experiences.

Regrettably, interpreting students often enter IEPs having limited engagement with the community where they hope to work; however, service-learning has the potential to help bridge the disconnect between interpreting students in the classroom and the community in which they will work. With the shift to academic training of interpreters it is important to foster ways students form relationships with members of the Deaf community. American Sign Language (ASL)-English interpreting did not originate as an occupation but rather as a way to meet the expectations of reciprocity to the Deaf community. Historically, individuals interested in the field of ASL-English interpreting were already a part of the Deaf community and chosen, trained, and deemed ready for interpreting by those same members of the Deaf community (Cokely, 2005). However, with the formation of the RID, the passing of disability rights legislation in the 1970s and beyond, and the formal training of interpreters through academic institutions, it has largely become those institutions who are now in charge of the selection and training of potential interpreters (Cokely, 2005). Using our past to help shape the future of the profession and to preserve the value of community engagement in interpreting requires a paradigm shift in how students are educated. Service-learning is a way to connect students who enter the field as a product of academic training, while striving to embody the values of being an interpreter “of the community” (Cokely, 2005, p. 25).

Service as a Way of Giving Back

The idea of service, or giving back, to the Deaf community is an important part of the work we do as professional interpreters. This belief of giving back through service is evident in the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf – National Association of the Deaf (RID-NAD) Code of Professional Conduct (CPC). Relationships that foster civic responsibility and partnerships with the Deaf community are key to developing cultural competence and understanding community values. This is an opportunity for students to explore and understand bias through structured learning with self-assessment, reflection, feedback, revision, and practice, which are essential for self-awareness and improvement. Students in the classroom as well as emerging interpreters “who have yet to internalize a code of professional conduct will learn from service learning that it is possible to form community alliances and still be professional practitioners” (Shaw, 2013, p. 6).

Service-learning is more than the act of providing a form of community service, or participating in fieldwork, an internship, or practicum for a class. The National Service-Learning Clearinghouse (NSLC) describes it as “a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities.” Monikowski and Peterson (2005) explain it is a pedagogical method where students earn academic credit while providing service to the community. Students can practice, reflect on, and refine decision making through community engagement. This is a wonderful opportunity for emerging interpreters to apply decision-making approaches such as Demand-Control Schema. Areas of overlap for SL and DC-S that also help us fill in the “it depends” include:

Case Conferencing

One way exploration of “it depends” is possible through the structured reflection of case conferencing , which can be employed, not only to an interpreted interaction but also with a myriad of service activities/interactions (Dean and Pollard, 2011). Case conferencing also facilitates the practice of maintaining confidentiality not as secrecy but through structured supervision to develop an understanding of how to talk about the work and decision making to promote growth (Dean and Pollard, 2001). In turn, service learning and DC-S provide the structure by which we could engage in meaningful, professional and constructive dialogue to improve the work by reflection-on-action, which would eventually inform the ability when engaging in reflection-in-action (Dean and Pollard, 2011).

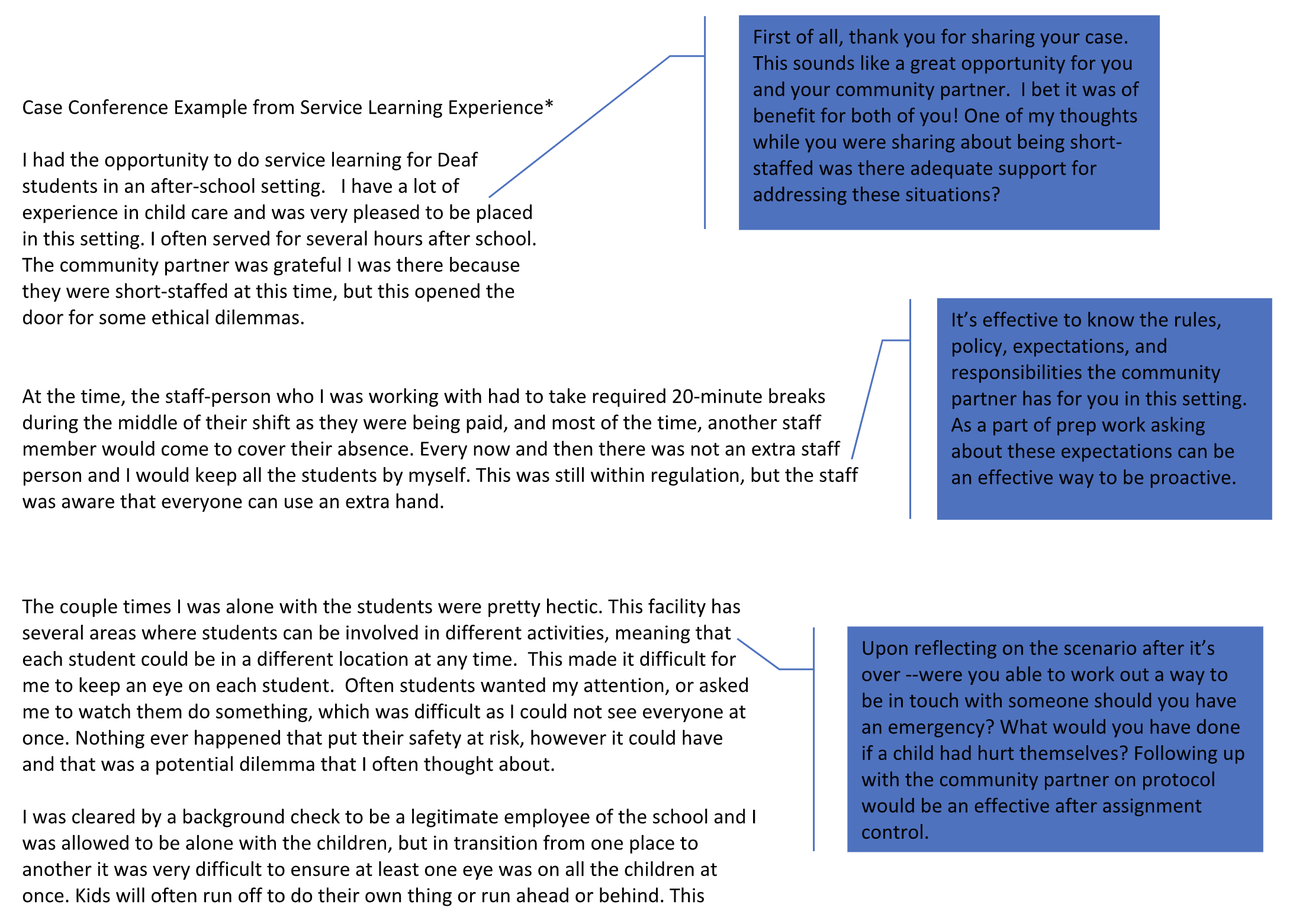

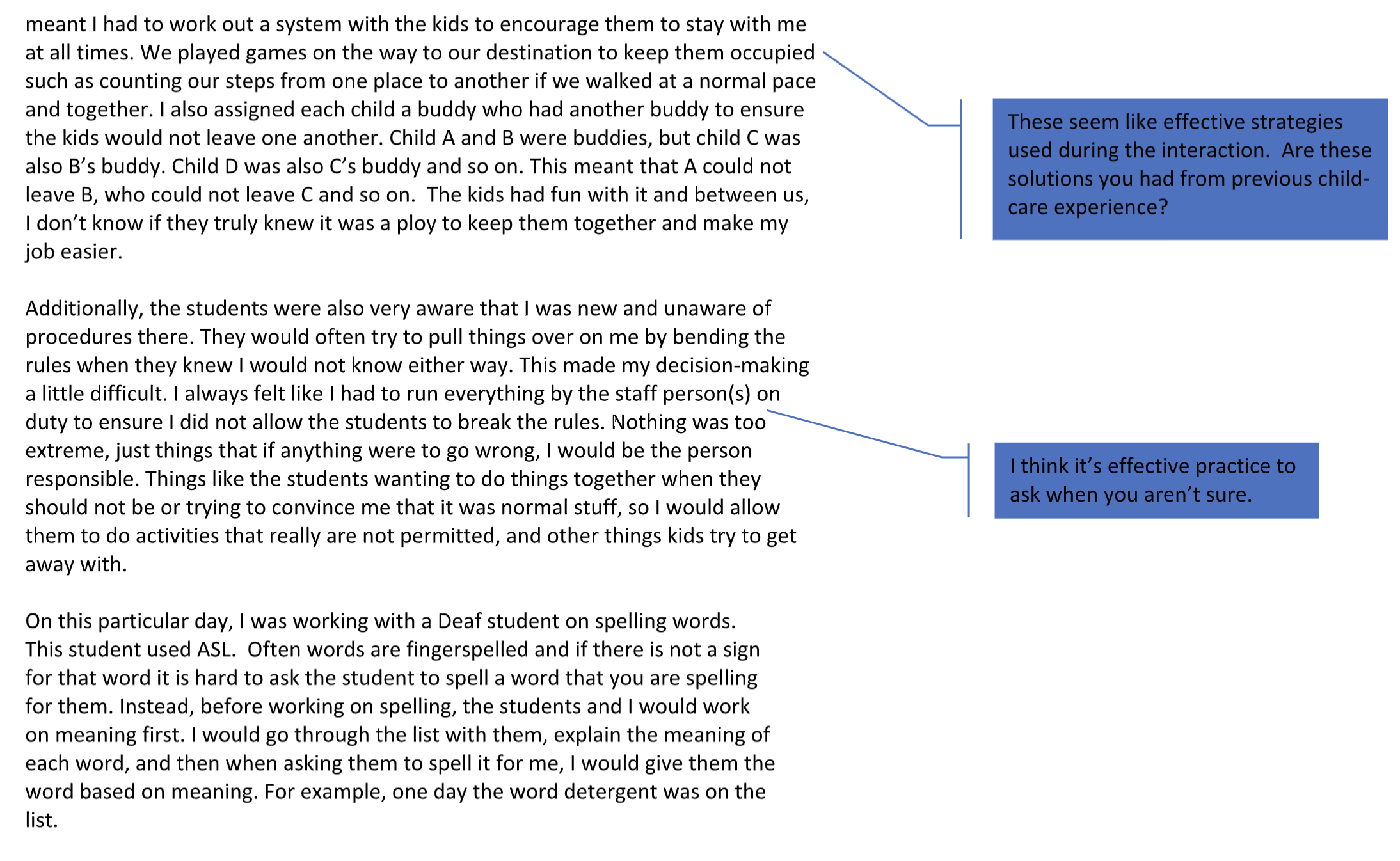

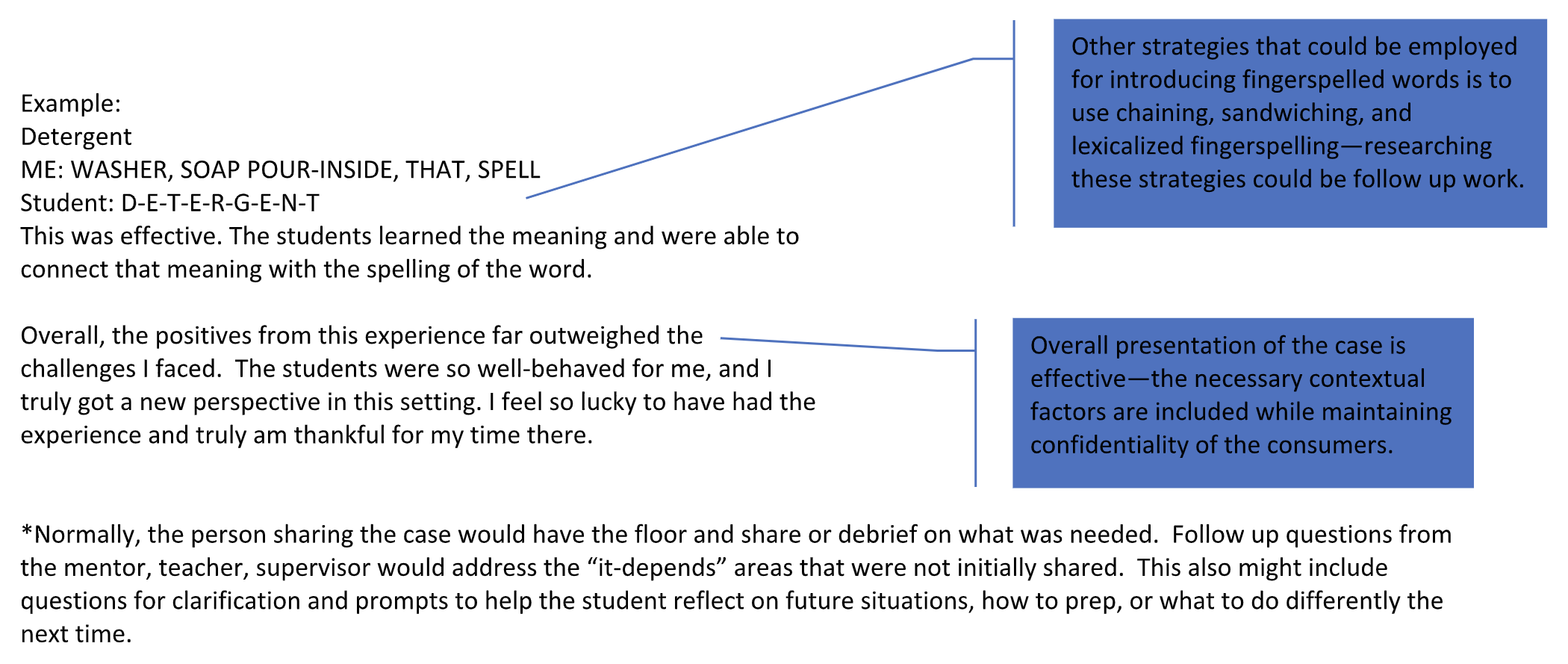

Below is an example of a case conference from an interpreting student taking part in a semester-long service learning project. Based on community and individual assets the student was placed as a volunteer in a local educational setting. The case is based on an actual experience and the instructor comments (while not the exact case and comments given during class) reflect the similar intent while modeling a way to approach case conferencing. Ideally, during case conferencing, the person sharing would have the floor as others attend to the case. The main paragraphs have the case and the bubbles indicate instructor response:

Collaborative learning environments, such as service learning, provide a way for students, practitioners, and community partners to work together. Rich learning opportunities can be paired with a decision-making construct, such as DC-S. These valuable tools are an effective way to help educate emerging interpreters. These tools can help students gain more from service experiences when given a chance to apply course content to real-world, everyday situations of a professional interpreter. The application of DC-S in service learning settings provide genuine experiences with authentic learning opportunities that are mutually beneficial for those involved, simultaneously drawing us back to the roots of vetting interpreters.

Resources

Ames, N., & Diepstra, S. A. (2006). Using intergenerational oral history service-learning projects to teach human behavior concepts: A qualitative analysis. Educational Gerontology, 32(9), 721-735. doi:10.1080/03601270600835447

Baker, S. (2010). Research brief no. 1: The importance of fingerspelling for reading.

NSF Science of Learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning. https://vl2.gallaudet.edu/files/7813/9216/6278/research-brief-1-the-importance-of-fingerspelling-for-reading.pdf

Cokely, D. (2005). Shifting positionality: A critical examination of the turning point in the relationship of interpreters and the deaf community. In M. Marschark, R. Peterson & E. A. Winston (Eds.), Sign language interpreting & interpreter education: Directions for research and practice (pp. 1-28). Oxford University Press.

D’Agostino, M. (2010). Measuring social capital as an outcome of service learning. Innovative Higher Education, 35(5), 313-328. doi:10.1007/s10755-010-9149-5

Dean, R. K., & Pollard Jr, R. Q. (2001). Application of demand-control theory to sign language interpreting: Implications for stress and interpreter training. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 6(1), 1-14.

Dean, R. K., & Pollard Jr, R. Q. (2011) Context-based ethical reasoning in interpreting. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 5(1), 155-182, DOI:10.1080/13556509.2011.10798816

Dean, R. K., & Pollard, R. Q. (2013). The demand control schema: Interpreting as a practice profession. CreateSpace.

Harkavy, I., & Hartley, M. (2010). Pursuing Franklin’s dream: Philosophical and historical roots of service-learning. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(3/4), 418-427. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9341-x

Kiraly, D. (2000). A social constructivist approach to translator education: Empowerment from theory to practice. St. Jerome.

Monikowski, C. & Peterson, R. (2005). Service learning in interpreting education: Living and learning. In M. Marschark, R. Peterson & E. A. Winston (Eds.), Sign language interpreting & interpreter education: Directions for research and practice. Oxford University Press.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Shaw, S. (2013). Service learning in interpreter education: Strategies for extending student involvement in the deaf community. Gallaudet University Press.

Witter-Merithew, A. (2001). Feedback: A conversation about ‘the work’ between learners and colleagues. Retrieved from https://www.unco.edu/marie/pdf/archived-literature/Feedback-Conversation-About-Work.pdf

About the Authors:

Tara Stevens, M.Ed., CI and CT, Richmond KY is an Assistant Professor in the Department of ASL and

Tara Stevens, M.Ed., CI and CT, Richmond KY is an Assistant Professor in the Department of ASL and

Interpreter Education at Eastern Kentucky University. She’s a doctoral student in the

Department of Interpretation and Translation at Gallaudet University and holds a M.Ed. in

Interpreting Pedagogy from Northeastern University. Research interests include study of the

psychological profile and cognitive aptitudes of interpreters, language attitudes, and service

learning.

Amy Schilling, ABD, CI and CT, Richmond KY holds a BA in Deaf Education from Eastern Kentucky

Amy Schilling, ABD, CI and CT, Richmond KY holds a BA in Deaf Education from Eastern Kentucky

University, a MA in Interpretation from Gallaudet University. She is currently pursuing her EdD

in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at EKU. Amy has been interpreting professionally

since 2004 and is currently working as an Assistant Professor in the American Sign Language

and Interpreter Education Department at EKU. Amy is passionate about her students and

enjoys life-long learning.

Both Tara and Amy hold a strong belief in giving back to the community and combined serve +300 hours annually. In the past year they have served on the KYRID board, volunteered with the Kentucky Association of the Deaf-Blind, and other community groups/events.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.